Zhao Songting

I. The Prodigy from Dongxi

Born in Shangyuan Village—a place teeming with talent where every household molded clay and crafted teapots—Zhao Songting entered the world to the rhythmic sound of clay being beaten. Some legends suggest his family was not native to Shangyuan but had migrated from elsewhere, possibly Zhenjiang or Jingjiang. Regardless, his birth coincided with the decline of the Zhao family’s fortunes. His father, a strict scholar-teacher, clung to the pride of their former elite status, relentlessly drilling young Songting in classical texts like the Three Character Classic, A Hundred Family Surnames, and Thousand-Character Essay. By the time he enrolled in the Shushan Dongpo Academy, his scholarly prowess was evident, and he consistently topped the county’s literary exams.

At 16, his father’s death forced Zhao to abandon scholarly ambitions and apprentice under Shao Futing, a descendant of the legendary Shao Daheng lineage of teapot makers. Mastering foundational styles like Bamboo Drum and Duo Qiu, Zhao became a skilled artisan, though life remained frugal. His breakthrough came with the Hidden-Angle Bamboo Drum Teapot, a bold redesign of Fan Zhang’en’s classic. Its acclaim caught the eye of Wu Yueting (art name Zhuxi), a master engraver who, though refusing formal discipleship, mentored Zhao in carving techniques. Adopting the art name Dongxi (after the stream near his home), Zhao began signing his works, reigniting his dormant artistic dreams.

II. The Legacy of Shao and the Patronage of Wu

Shangyuan Village, though humble, attracted connoisseurs like Wu Dacheng, a high-ranking official and zisha enthusiast. Through Wu Yueting’s connections, Zhao’s talent reached Wu Dacheng, who invited him to Suzhou in 1893. Immersed in Wu’s collection of ancient bronzes and ceramics, Zhao honed his craft, blending classical motifs with innovation. Signing works as Zhiquan (“Branch of the Shao Spring”) to honor his roots, he created elegant, minimalist teapots and even pioneered the Zisha Tile-Shaped Pillow—a fusion of poetry and carving that expanded the art form’s boundaries. Collaborations with masters like Huang Yulin and Yu Guoliang further elevated his status.

Behind the scenes, Zhao observed Wu’s dealings with Shanghai merchants, absorbing business acumen that would later prove invaluable.

III. Innovation and the Maritime Silk Road

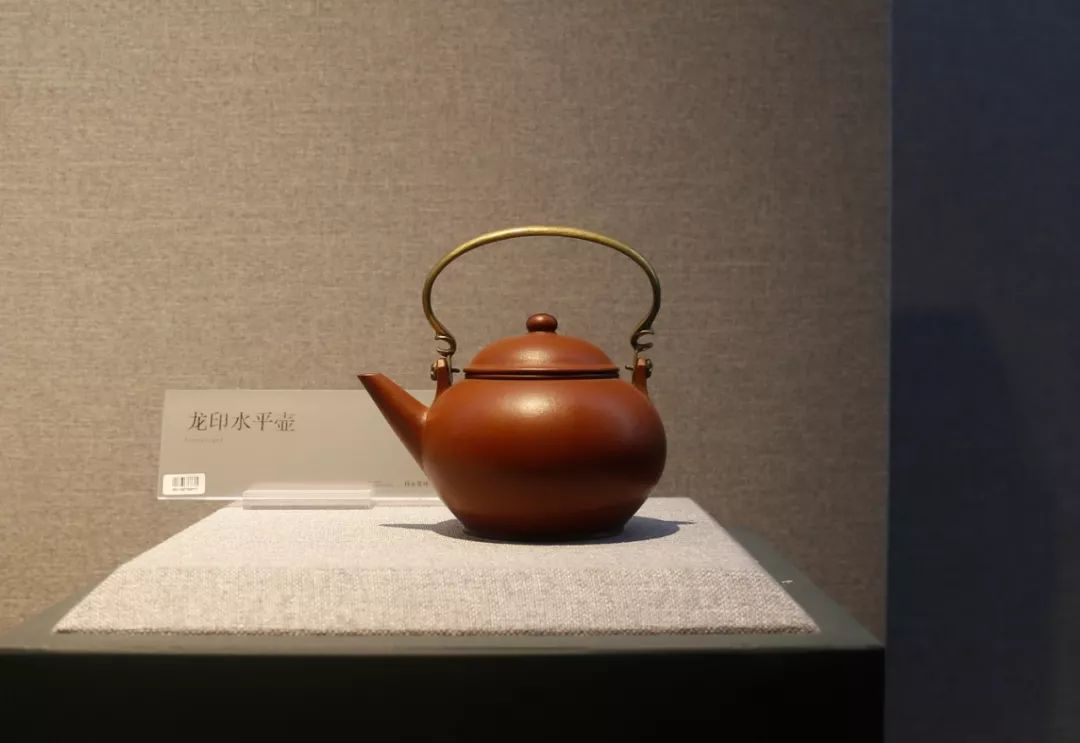

Foreseeing turmoil before the First Sino-Japanese War (1894), Zhao returned to Shangyuan, scaling production to meet booming demand. By 1905, he mentored his son Zhao Qiantai and established a workshop, hiring top artisans like Chu Ming (renowned for Foreign Bucket Teapots) to supply exports to Southeast Asia. His Tribute Series (“Gongju”), crafted by a team including future master Wang Yinchun, dominated Shanghai’s foreign concessions and overseas markets.

In 1925, amid warlord chaos, Zhao gambled his fortune to build Revival Kiln, producing Tribute Teapots that blended antique appeal with clever branding. By the 1930s, his enterprise spanned 40 workshops, cementing his legacy as both artist and industrialist.

Epilogue: The Scholar-Artisan

Zhao Songting (1853–1934) stood apart as a zisha carver, calligrapher, and painter whose works exuded scholarly refinement. His collaborations with Wu Dacheng yielded treasures now housed in museums, while his business savvy revolutionized the craft’s commercialization. From the Dongxi engravings to the Zhiquan seals, each mark told a story of tradition and reinvention—a testament to a man who bridged art and enterprise in China’s tumultuous late imperial era.